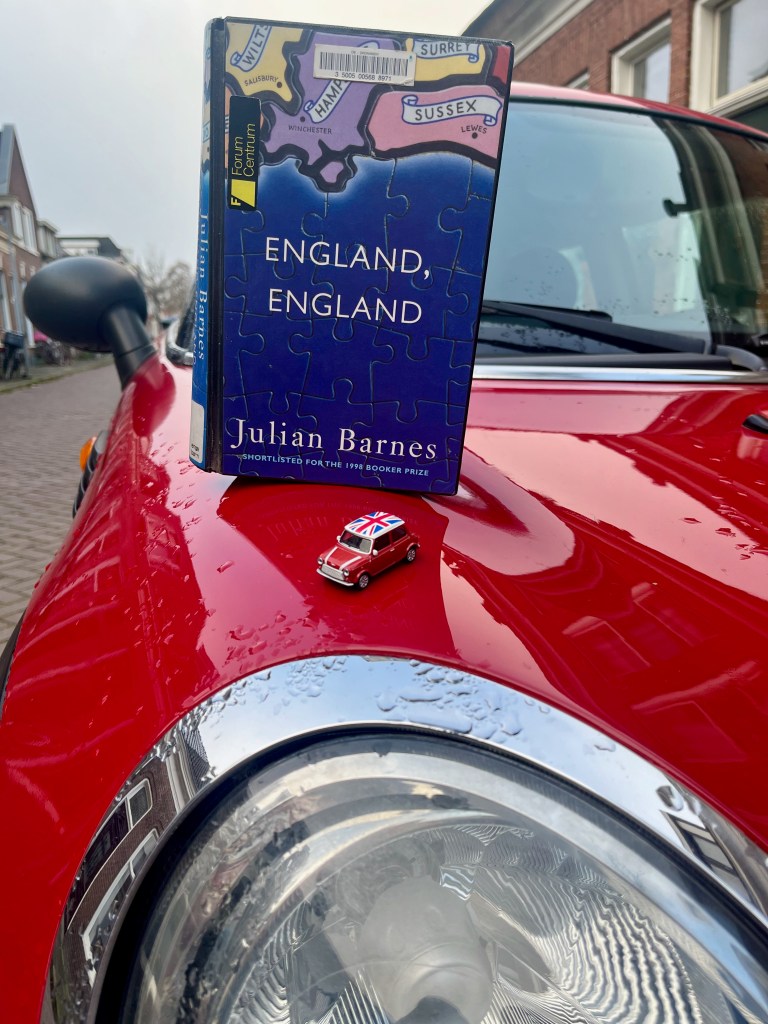

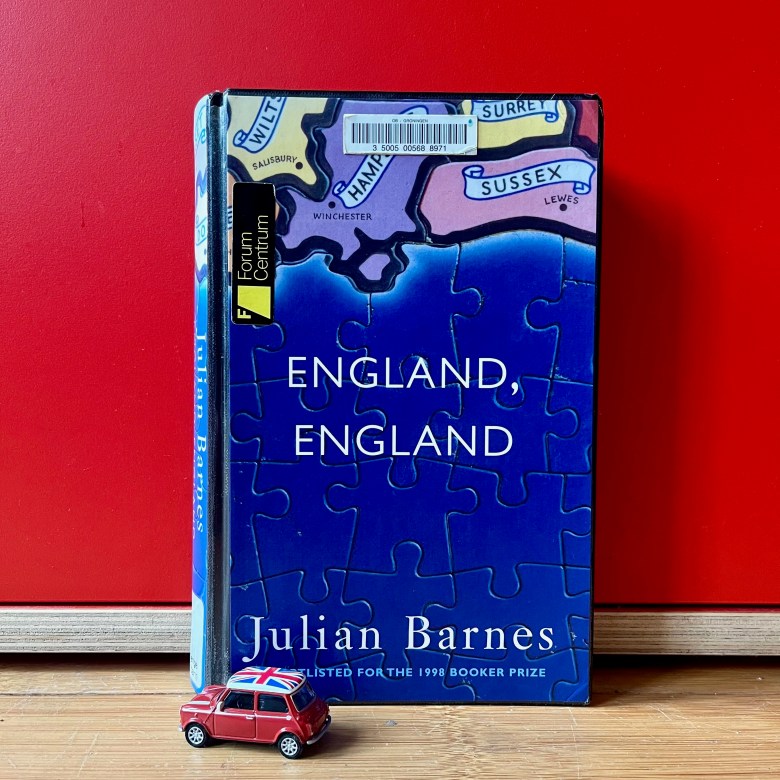

There’s a book for every occasion. Whatever you do, whatever you’ve been through, there’s a novel that mirrors your own life. Last weekend, I gave lectures about Charles Dickens at a nineteenth-century Christmas fair, dressed up as a Victorian reporter. At one point, enjoying some time on my own, I found myself sitting quietly in a corner reading Julian Barnes’s England, England. I could not have picked a book better suited for that situation. Want to know why? Read on!

England, England starts with a description of protagonist Martha Cochrane’s childhood, then switches to the future, in which millionaire Sir Jack Pitman decides to create a smaller, more convenient version of England on the Isle of Wight, with only the interesting bits in it, in order to draw as many tourists as possible. Martha is the amusement park’s manager. What happens next is an analysis of power, blackmail, and a search for identity. And of England, of course – both the real England and the smaller one on the Isle of Wight.

In England, England, a questionnaire is set up in order to find the true essence of England. Then a list is drawn of all the quintessentially English things that should be displayed on the Isle of Wight, later redubbed England, England. Buildings are replicated, actors are hired, and histories are rewritten to prevent possible embarrassment. And of course, it turns out to be a huge success; people from all over the world are willing to spend a fortune on spending time in this more convenient version of England.

I was reading Barnes’s novel while I was on a break from the lectures I was giving in Deventer during their annual Dickens Festival. Every year before Christmas, this Dutch city transforms into a nineteenth-century version of England. Volunteers dress up, sing Christmassy songs, make traditional Victorian food, and act like they really lived over a hundred and fifty years ago. I was there talking to people who wanted to learn something about Charles Dickens – dressed up, too, pretending to be a nineteenth-century journalist.

In two days time, I had to give nine lectures of fifteen minutes each. It was cold and I was tired, so at one point I decided to take a break and retreat into a book. As fate would have it, I had brought England, England, and while reading I could not help but be amazed at the similarities between this novel and the situation I was in. Deventer, like the miniaturised version of England, has strict rules about how everything should look, how participants should behave, and how everything should be as authentic as possible. But what, exactly, does authentic mean?

Both Deventer and the new England in the novel share the idea that one person can decide what authenticity is; the festival in Deventer was set up by Emmy Strik, a woman who decided that she wanted her city to be more festive and was inspired by Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol. However, while walking around there I noticed how her Victorian England is based on the idea we have of Victorian England; it is a jolly place, a heart-warming, Christmassy place, a modern, romantic, convenient version that only resembles the Victorian era because we like to think it does.

My lecture was on Charles Dickens’s creative mastery of the language, and more specifically the way he insulted people without using any bad words. The Victorian age was one which was obsessed with proper behaviour, which means that people would never curse, had to adhere to very strict rules, and Bowdlerised art. This means that they made everything more appropriate to the Victorian people, such as removing parts of Shakespeare’s works or placing fig leaves on naked statues. In the introduction to Oliver Twist, Dickens wrote that he would show the real dregs of society, but he would change the language so it would not be “offensive to the ear”. And there we have it: the essence of both England, England and the Dickens festival in Deventer.

Apparently, amusement should be simple and easy. While enjoying ourselves, we don’t want to worry about insulting anyone or being politically incorrect. England, England in Barnes’s novel is conveniently small, and folklore has been changed so it would be more inclusive. In Deventer, we shouldn’t worry about misogyny, about horrible conditions for the working classes or high mortality rates. So while I was reading England, England, wearing a dress and a large hat (my short hair was shockingly anachronistic, so I had to cover it up), I sometimes laughed out loud because it often felt like I was doing exactly that which is ridiculed in the novel. As long as people are entertained, it doesn’t matter whether things are genuine or not.

Regarding entertainment and authenticity, some time ago, a study was done on whether people are able to discern real poetry from poems written by AI. It turns out that this is harder than one thinks. Furthermore, most people preferred the AI-generated poems, because they used simpler vocabulary and their meanings were more straight-forward. Apparently, even when it comes to poetry, people prefer convenience over authenticity.

In England, England, everything goes wrong in the end; Old England (as it’s called) falls to ruins and its smaller version becomes faker and faker – but still it’s enormously lucrative. Obviously, I hate this, and you may wonder why on Earth I agreed being part of the Dickens festival, and why I said I wouldn’t mind dressing up as a nineteenth-century journalis and contributing to the notion of convenience and history and art as amusement. However, I like to think I’m working the system from within, teaching people something about real history, and real art, and the real Charles Dickens. Everyone left being just a bit smarter than they were.

It goes without saying my lecture was hugely entertaining, too.

What did you think of England, England? Do you think we really prefer convenience over authenticity? Do you think we should work harder at knowing the truth of things? What is important to you when you want to be entertained? Would you ever consider going to the Dickens festival in Deventer, or a smaller version of England? Do you think my book really suited the occasion, or do you think I changed it so it was more convenient? Please let me know in the comments! Also, don’t forget to follow me for more book-related posts!