“For most of history, Anonymous was a woman.”

This modified quotation by Virginia Woolf shows her annoyance at the lack of great female authors. That’s because literature used to be a strictly male discipline. This I knew. What I wasn’t aware of, however, was that literature’s medium, words and language, used to be male-dominated, too. Therefore, Pip William’s novel The Dictionary of Lost Words, which is about the creation of the very first Oxford English Dictionary, was an eye-opener. Want to know why? Read on!

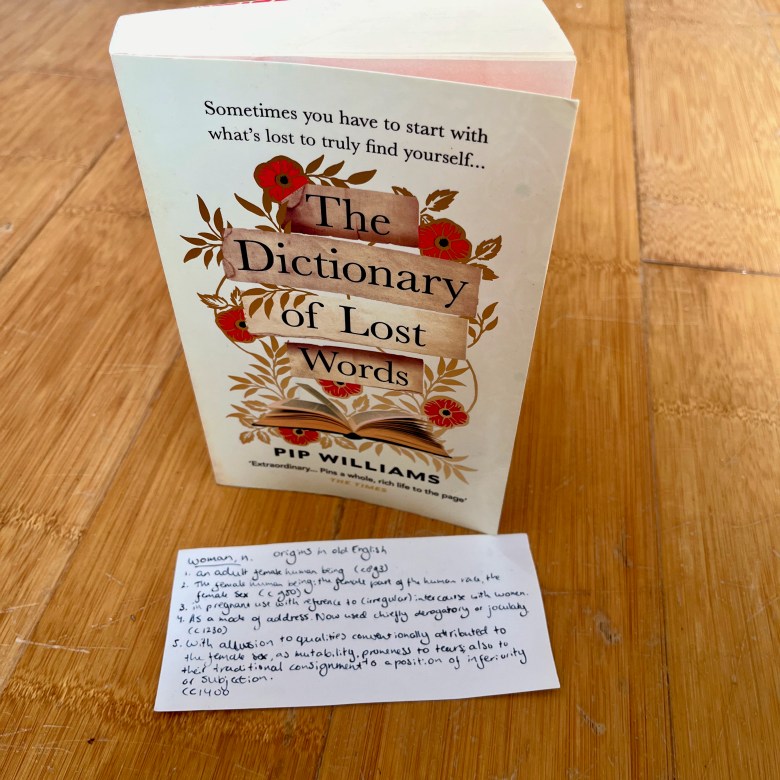

The Dictionary of Lost Words is about Esme, whose father is an editor of the soon-to-be-published-but-actually-already-long-overdue Oxford English Dictionary. Since her mother died, Esme spends her days at their office, watching men work, and keeping an eye out for words that might not make it to the final edition. The story starts when five-year-old Esme picks up the word bondmaid, and doesn’t return it to the editor who dropped it to the floor. She keeps the word, and as she grows older, starts wondering about its meaning. She then decides to start a collection of words about and by women.

The Dictionary of Lost Words is a novel about how history has always been written by men. The word bondmaid makes Esme realise that women have never truly been part of this dictionary – nor hardly of the English language itself. That’s because in the first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary, words were only included in the dictionary if they had a written source, and the large majority of these sources were written by men. A couple of noteworthy exceptions aside, women didn’t write books, and therefore were not recognised as the creators of new words.

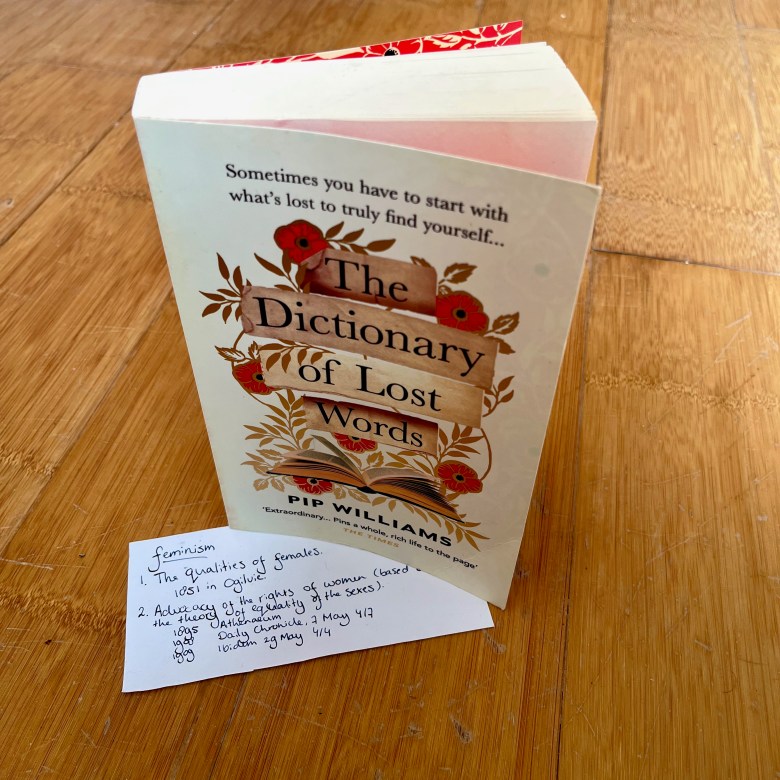

Much of what happens The Dictionary of Lost Words was based on actual events; the editor-in-chief was a real person, the glorified shed where the editors of the Oxford English Dictionary worked, ironically called the Scriptorium, really existed, and the word bondmaid wasn’t included in the first edition of the OED. Ms Williams took these historical facts and used it to raise the following question: do words mean different things to men and women? Fictional protagonist Esme realises that, of course, the answer is yes. When Esme grows up, she becomes friends with a girl who calls herself a suffragette, and while Esme doesn’t actively support the cause, she does show her loyalty to women in another way: she compiles her very own dictionary, filled with words used by women, words that aren’t in the Oxford English Dictionary because men consider them useless.

Reading The Dictionary of Lost Words made me wonder, again, whether I am really a feminist. I have stated before that I don’t consider myself a true feminist, since I don’t go on marches, and I don’t exclusively read books by female authors, for instance. However, I do feel proud whenever I read about female achievements. Likewise, this novel made me realise how much the world has changed in a hundred years, and how much courage women must have needed in order to stand up to men, to make demands that were unheard of at the time.

This novel reminded me of another feminist novel set in the suffragette era: The Once and Future Witches by Alix E. Harrow. While this is a fantasy novel, there are clear parallels between the notion that there are male and female words; however, Harrow poses the notion that words need to be shared in order to be powerful – more powerful, indeed, than men’s words – while The Dictionary of Lost Words presents the idea that the words need to be put to paper in order to be remembered. Because Esme writes down all these women’s words, women are given a voice when they were usually silenced.

The current edition of the Oxford English Dictionary is very different from its very first publication. The world has changed almost unrecognisably in a hundred years, and so has language. I must admit I’m kind of a language snob; I always want to use the proper word, and the proper spelling, and I hate so-called internet language. However, having read The Dictionary of Lost Words, I realise that my thinking this way makes me snobbish in much the same way as the men creating the first Oxford English Dictionary. I should accept that language is not fixed, and sometime words change meaning, or stop being used altogether – like that one word which this novel started with: bondmaid.

We use words to define ourselves. Identity is never fixed, so it only makes sense that language evolves with us.

What did you think of The Dictionary of Lost Words? Do you think it’s a good thing that language always changes? Which word, do you think, means something different for men and for women? What is your favourite word, and why? Please share in the comments! Also, don’t forget to follow me for more book-related posts!

Hoi Elke, Misschien vind je dit leuk > https://www.ft.com/summerbooks22?emailId=62b40c65d81b7b00236c8a9a&segmentId=72adc702-369e-fc3e-1b5d-cacb5d193d80 Ik weet alleen niet zeker of je er toegang toe krijgt, maar niet geschoten is altijd mis! Groetjes, Aleid

LikeLike

Ha Aleid, dat is zeker heel leuk! Dank je voor de tip! Groeten, Elke

LikeLike